“How to make site-specific art when sites themselves have histories: Whittier Boulevard as Asco’s camino surreal”

On August 26, Carmelites commemorate the “piercing” of St. Teresa’s heart by an angel. In her autobiography, she writes how she “saw in his hand a long spear of gold,” which he thrust “at times into my heart and to pierce my very entrails.” “The pain was so great,” she continues, “that it made me moan; and yet so surpassing was the sweetness of this excessive pain, that I could not wish to be rid of it.” It’s difficult to ignore the sexual undertones of St. Teresa’s description of this experience, immortalized in Bernini’s Ecstasy of Saint Teresa. From its obsession with the Virgin Mary to its longstanding requirement for a celibate clergy, the Catholic Church has something of a fixation on sex, prompting Pope Francis to lament the Church had become obsessed with abortion, contraception, and same-sex marriage, to say nothing of the sex abuse scandal that rocked the Vatican for decades and implicated thousands of priests. But throughout its history, the Catholicism has been associated with a sexual morality that elevates the “charmed circle” of monogamous heterosexual coupling over all other forms of human intimacy. Although the Church’s positions on sexuality may be the most visible manifestation of its politics, it’s far from the only one. To be sure, Catholics have been a powerful conservative force across much of the globe, from their opposition to the French Revolution to their support of the Francoist dictatorship in Spain. Alongside this history, however, runs the countercurrent of Catholic social teaching, such as within the Catholic Worker Movement founded in NYC by Dorothy Day and Peter Maurin at the nadir of the Depression. These developments were especially pronounced in Latin America in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, when theologians like Gustavo Gutiérrez, Leonardo Boff, Juan Segundo, and Jon Sobrino drew inspiration from the Sermon on the Mount to defend a “preferential option for the poor.” Liberation theology, as it came to be called, emphasized “integral mission,” stressing both evangelism and social responsibility.

These ambivalent political legacies of Catholicism help us to make sense of the use of religious imagery within Chicano art. In this article, I focus on Asco, a Chicano collective active in East LA from 1972 to ’87 initially composed of Harry Gamboa, Jr., Glugio “Gronk” Nicandro, Willie F. Herrón III, and Patssi Valdez. Working primarily within performance, the members of Asco, grew up during the Vietnam War, which many Chicanos in the Los Angeles area believed was killing them at a disproportionate rate. Indeed, Gronk cites the Vietnam War as inspiring Asco’s name. In his words, “a lot of our friends were coming back in body bags and were dying, and we were seeing a whole generation come back that weren’t alive anymore. And in a sense that gave us nausea—or ‘nauseous.’” To protest Vietnam, Chicano activists banded together to form the Chicano Moratorium. This group organized the National Chicano Moratorium March along Whittier Boulevard to voice their disapproval of the War and its effects on their community.

A major commercial corridor in East LA, Whittier Boulevard from the LA River to Brea. Not only was Whittier Boulevard the location of much community activity but it also connected the Eastside to the heart of LA. Several of Asco’s performances over the years occurred along Whittier Boulevard. Regarding the street’s importance to Asco, Herrón reminisces,

At the time of the Moratorium, I was in high school. I remember the procession originating at Belvedere Park, protesting the Vietnam War and all the Chicanos that lost their lives. The police brutality was incredible. It affected me quite a bit and I think it affected all of us. So that’s why Whittier Boulevard became such an important street, and a place for us to conduct our performances and connect them to our community and the way society viewed us at the time.

We can see in this quote the double role Whittier Boulevard plays as symbolizing both the reality and reputation of East LA, as well bridging the Chicano barrio and the Anglo art world, between which Asco would continually navigate.

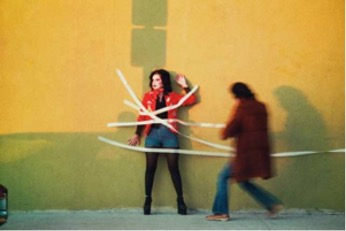

But if we take a longer view of the history of this area of what is now the Southwestern US, we can see yet another dual role for Whittier Boulevard, which carries a portion of el Camino Real that connected the mission of Alta California, a province of New Spain. Gamboa even “used the phrase ‘el camino surreal’… to describe Whittier Boulevard as the setting where everyday reality could quickly devolve into absurdist, excessive action.” Indeed, the coloniality of the Camino Real is a crucial element of these pieces, insofar as the tension between imposition and conversion is key to the acceptance and reproduction of national values. By foregrounding Whittier Boulevard, we can see that rather than making simple “protest art,” Asco demonstrated a deep awareness of the historical forces excluding them from both the Latino communities of East LA and the Anglo art world downtown and on the Westside. In two performances, Stations of the Cross and First Supper (After a Major Riot), Asco mimicked Catholic rituals to compare their experiences as racial minorities with the conquest of the Americas, thus politicizing a religion often blamed for the supposed traditionalism of Mexican Americans. Two other performances, Walking Mural and Instant Mural, poked fun at muralism, thus calling attention to the ghettoization of Chicano art. Indeed, Asco’s first piece, Spray Paint LACMA, involved tagging the entrance of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art in protest against a curator who explained he didn’t acquire Chicano art because Chicanos were only capable of “making folk art and joining gangs.” Although ostensibly unrelated to Catholicism, I intend to show how indebted muralism is to religious iconography, and how Walking Mural and Instant Mural continue these explorations.

Despite their differences, these performances share similar strategies; namely, a process of defamiliarization the Situationist International dubbed détournement, defined as:

The integration of present or past artistic productions into a superior construction of a milieu. In this sense there can be no situationist painting or music, but only a situationist use of those means. In a more elementary sense, détournement within the old cultural spheres is a method of propaganda, a method which reveals the wearing out and loss of importance of those spheres.

By resignifying religious and muralist imagery, Asco inhabits Chicano stereotypes to test their limits, and even violate them. Although meaning cannot be created ex nihilo, by representing history Asco makes room for what we might call the multivocality of site. Like all places, Whitter Boulevard has a historical residue available for reactivation. Through performances that bring the past into the present, Asco demonstrates how to make site-specific art when sites themselves have histories.