“Icon, Idol & Fetish: Iconoclasm & Theopolitical Justice in the Palestinian Borderlands of Bethlehem”

Connie Gagliardi

My doctoral dissertation research explores the contemporary crafting and cultural production of traditional Christian icons amongst iconographers in Bethlehem, Jerusalem and the Christian Holy Land. Methodologically employing Bourdieu’s framing of the “field” to consider the “space of activity” of Christian icons, my dissertation charts a visual culture of Christian iconography in Palestine, tracing the creation, production and emplacement of icons within and upon the fractured contemporary Palestinian landscape. My chapters attend to the making of icons by Palestinian Christian iconographers, and their lifewolds; while others take the locally-made Palestinian icon as their ethnographic object. In shifting between icon-as-subject and icon-as-object, my dissertation captures the oscillating rhythms and movements of a “theos” in movement (Napolitano 2020) and the political implications of its theopoiesis.

Figure 1: The “Pantocrator Christ” of the Emmanuel Melkite Monastery, Bethlehem. Image taken by author.

As part of my dissertation’s final chapter, “Image, Idol & Fetish” is an experimental ethnographic project, as it seeks to draw out how “theology partakes in a history of materiality of everyday life” (McAllister & Napolitano 2020). More specifically, it attends to the socio-historical resonances of the long theological durée and debate over images, icons, idols and fetishes, as they are pushed into the present. Rooted in an ethnographic inquiry into the “politics of aesthetics”, this project considers the iconic and idolatrous images that appear and are destroyed upon the face of the Israeli Separation Wall in contemporary Bethlehem, in the Occupied West Bank.

What makes this project “experimental” is the ways in which it brings together two, separate ethnographic and aesthetic examples – the perseverance of the icon of “Our Lady Who Brings Down Walls”, and the proliferation of defacements of the street art of Lushsux – to draw out these theological tensions. Briefly historicizing “iconoclasm” within the “populist” appeals of Byzantine emperors, and against the “modernizing, purifying” desires of Martin Luther’s Reformation, this paper mobilizes these histories as they reverberate within the Bethlehem borderlands. This is because the Israeli Separation Wall is itself an infrastructure laden with fabulations of omnipotent Israeli sovereignty. The Wall is a fetish, glorifying the regime that built it, all the while maintaining colonial fictions that this is a naturalized border wall in the conflict (Gagliardi 2020; Taussig 1999). The space of the Israeli Separation Wall – which falls under full Israeli civil and military control, in its post-Oslo designation as “Area C”– is a derelict no man’s land in Bethlehem city’s margins. Herein lies a fabulated borderland of exclusionary and fictive state formation, where there is only the concrete face of the Separation Wall, the raw face of colonial power (Taussig 1998).

Figure 2: The Icon of “Our Lady Who Brings Down Walls”, 2013. Image taken by author.

Thus, for Palestinians, there is always some unease surrounding the images that appear upon the face of the Separation Wall, and the ways such images may mask the Wall’s fetish-power and help naturalize its presence. However, in the case of the icon of “Our Lady Who Brings Down Walls” (Figures 2 & 3), written on the Wall in 2011, it is the icon’s theological operations that make her imagery and semiotics permissible. The dynamic “life” of the icon of “Our Lady” forms the basis of my disseration’s first chapter, where I explore the ways in which Palestinian Christians believe her to be “alive”, sacralising the borderlands with the weight of divine presence. However, in this project I foreground her “transfigurative” theopolitical power to imagine a Palestinian “Otherwise”, as she lives and ebbs, presides and withdraws upon the face of the Israeli Separation Wall. It is precisely this “otherwise”, engendered through a haptic vision that emanates from the mediating figure of the Virgin Mary in Middle Eastern Christian-Muslim communalism (Heo 2018), that preserves her iconicity. Written upon the fetishized face of the Israeli Separation Wall, the iconic face of “Our Lady” is a theopolitical insertion into its political-theological fabulation, enfleshing an alternative formation of divine power.

Figure 3: The Icon of “Our Lady Who Brings Down Walls”, 2017. Image taken by author.

For Palestinian Christians, this theopolitical insertion is all the more powerful when one considers the operations of the Christian icon upon the believing beholder. This is because the icon mysteriously reveals how “the Word became Flesh” and inheres within all of God’s living creation. In this project, I only briefly gesture to these reverberations; but in my dissertation’s second chapter, which shifts ethnographically to explore the crafting of icons amongst Palestinian Christian students of the Bethlehem Icon School, I consider the liberatory possibilities of the icon’s theology for Palestinian Christian iconography students. Following the theology of corpus mysticum Christi, which “traditionally imagined the church as a body made of diverse Christian persons participating together in the shared sacrament of the Eucharist (Scheper Hughes 2020), Palestinian Christian iconographers come “to see and know Jesus” through the face that emerges through the very labour of their hands. Writing an icon in Palestine is thus a “theopoetics”, a realizing of the divine inherent and a realizing of one’s ability to become divine via the recognition of the face of Jesus. As the Catholic Church calls the Palestinian Christian community “living stones” of Jesus, in the making of icons, Palestinian Christians are shown exactly what this means. Subsequently, my third dissertation chapter continues this inquiry into the politics of the icon’s enfleshment, as it shifts to the icon workshop of Palestinian iconographer Johnny Andonieh. Here, I demonstrate how seeing oneself within the iconic flesh becomes explicitly theopolitical, as I explore the ways in which the iconographer must contend between the icon’s own political project of enfleshment of the corpus mysticum, and the “iconocratic” control of the image by the Church (Mondzain 2005; Buck-Morss 2013).

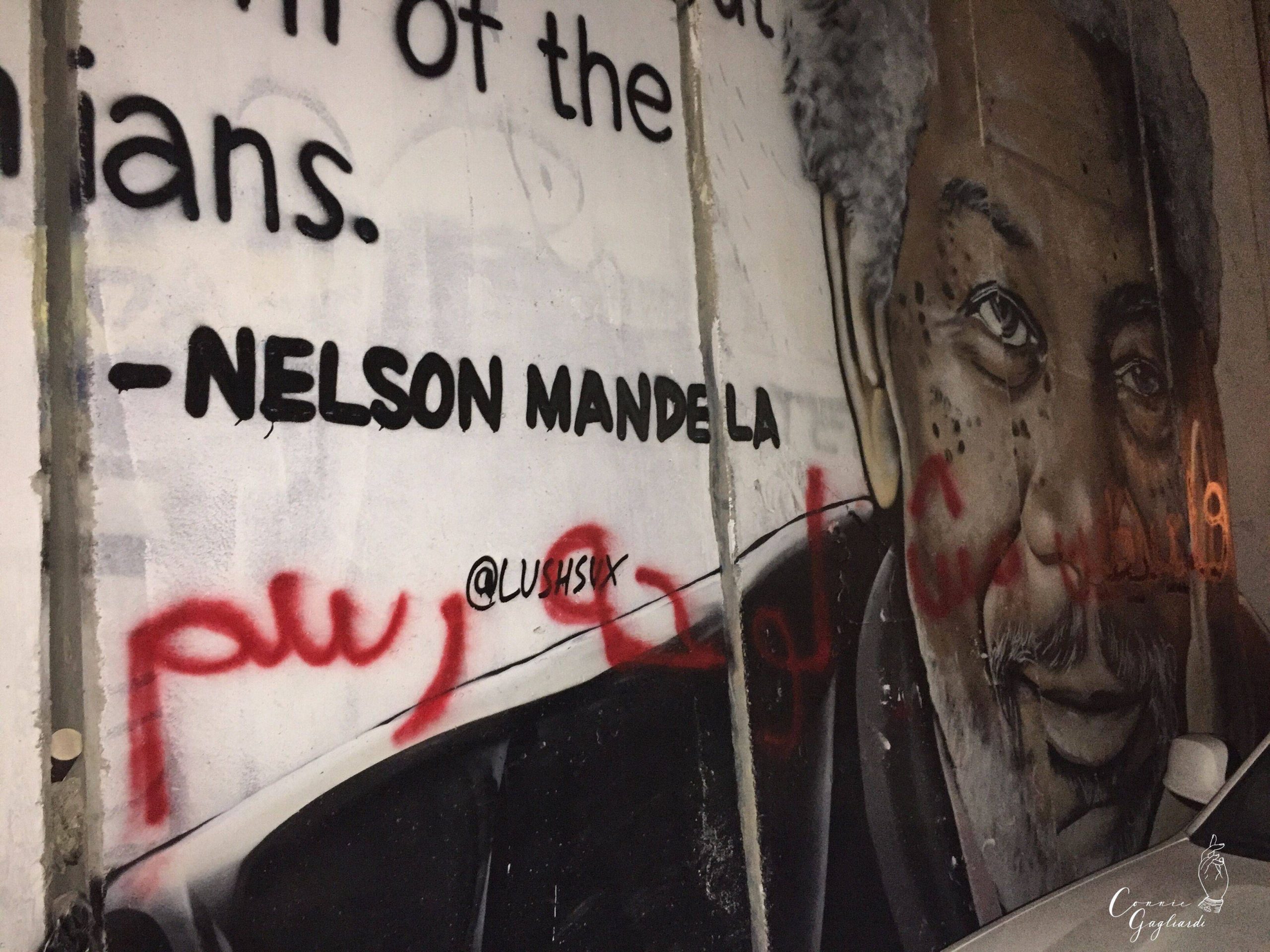

Thus, the icon of “Our Lady Who Brings Down Walls” operates within an explicitly Christian theopolitics that, in appearing upon (and withdrawing from) face of the Israeli Separation Wall, extends unto a radical theopolitics for communal imagining and thinking “otherwise”. But in the Fall of 2017, not far from the place of “Our Lady”, upon the very same face of the Israeli Separation Wall, there emerged a series of meme-murals and graffiti tags from Australian street artist, Lushsux, that could not proffer any radical imagining or alternative enfleshments of divine power. Instead, the meme-graffiti of Lushsux – which featured iconic faces of Western celebrity and right-wing politicians – slowly began to reveal an insidious metalanguage of alt-right politics that simultaneously affirmed the omnipotent political-theology of the Israeli state and its colonial fictions (Gagliardi 2020).

In response, a haphazard and motley crew of Palestinians – Christians and Muslims, young and old – took to the face of the Wall to destroy such “idols” upon the fetishized face of the Israeli Separation Wall. A proliferation of defacing acts, amounting to a public drama of iconoclasm, enacted the theopolitical operation of withdrawal, rendering Lushsux’ meme-graffiti void and mute and the Wall’s concrete materiality naked. Eerily sublime, the defaced meme-graffiti exposed the raw face of Israel’s political-theological power and all its fabulations (Figures 3, 4 & 5). Here, within the derelict space of the Wall, in Bethlehem city’s margins – a space marred by the monumentality of Israeli sovereignty – it was it was the “collective flesh” (Mazzarella 2019) of Palestinians deciding “icon” from “idol” from “fetish”, decisions that carry theological weight as they were once bestowed upon the sovereign himself.

Figure 4: The first defacement of Lushsux’s meme-graffiti: “Palestine is Not a Drawing Board”. Image taken by author.

Figure 5: The proliferation of defacements. “Palestine is on Both Sides of the Wall”. Photo courtesy of Jaclyn Ashly.

Figure 6: Defacements, enacting a public drama of iconoclasm. “Peace in Palestine is to throw guns at your occupier, and he puts them on your grave.” Photo courtesy of Jaclyn Ashly.

Works Cited

Buck-Morss, Susan. 2007. “Visual Empire.” Diacritics 37 (2–3): 171–198.

Gagliardi, Connie. 2020. “Palestine is Not a Drawing Board: Defacing the Street Art on the Israeli Separation Wall.” Visual Anthropology 33(5): 426 – 451.

Heo, Angie. 2018. The Political lives of Saints: Christian-Muslim Mediation in Egypt. Oakland: University of California Press.

Mazzarella, William. 2019. “The Anthropology of Populism: Beyond the Liberal Settlement.” Annual Review of Anthropology 48: 45 – 60.

McAllister, Carlota and Valentina Napolitano. 2020. “Introduction: Incarnate Politics beyond the Cross and the Sword.” Social Analysis 64(4): 1 – 20.

Mondzain, Marie-José. 2005. Image, Icon, Economy: The Byzantine Origins of the

Contemporary Imaginary. Trans. Rico Franses. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Napolitano, Valentina. 2020. “On the Touch-Event: Theopolitical Encounters.” Social Analysis 64(4): 81 – 99.

Scheper Hughes, Jennifer. 2020. “The Colony As The Mystical Body of Christ: Theopolitical Embodiment in Mexico.” Social Analysis 64(4): 21 – 41.

Taussig, Michael. 1998. “Crossing the Face.” In Border Fetishisms: Material Objects in Unstable Spaces, edited by Patricia Spyer, 224–44. New York, NY: Routledge.

Taussig, Michael. 1999. Defacement, Public Secrecy and the Labor of the Negative. Stanford, CA:Stanford University Press.