Conservative Christian Futures and Pasts: Exploring Infrastructures of Sovereignty and Display from Toronto to the U.S. Capital

Kyle Byron, Saliha Chattoo, Suzanne van Geuns, and Christina E. Pasqua

Part I:

The Project

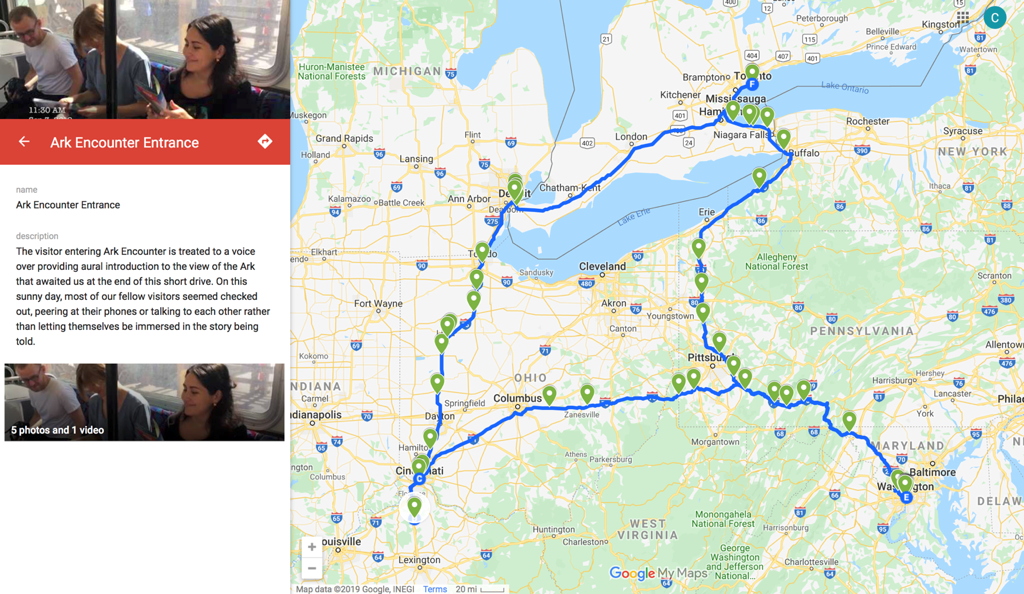

For the “Entangled Worlds” project, a team of four graduate students from the University of Toronto’s Department for the Study of Religion conducted a one-week research road trip to Washington, D.C. Kyle Byron, Saliha Chattoo, Suzanne van Geuns, and Christina Pasqua are anthropologists and historians of Christianity in North America. Together, they drove from Toronto, ON to Cincinnati, OH through Detroit, MI. They visited the Answers in Genesis Ark Encounter theme park in Williamstown, KY with Professor James Bielo before making their way to D.C., and later returning to Toronto through the Buffalo, NY border with Canada. Along the way, they documented various sites of religious and national display seen briefly from the road or explored during intensive daytrips, curating their audio recordings, videos, photography, written reflections, and tweets into a Google map that retraces their route.

Each day of the trip involved collective sightseeing related to the themes of the “Entangled Worlds” project: sovereignty, sanctities, soil. In addition to this focused collaborative work, each member of the team also conducted research at sites particular to their own dissertation topics. As such, the research trip was a journey across land and expertise, allowing each member to learn from one another in ways that their multimedia output catalogues — namely, through the curation of an interactive Google map and in the writing of ethnographic vignettes, which are included in part III and IV of this blog post. Before discussing how to navigate the map, it is important to first explain why a road trip to D.C. became the heart of this project.

As the U.S. capital, Washington, D.C. is not only home to the infrastructures of the nation’s political memory and identity (e.g., Lincoln Memorial, the White House), but it is also a cultural hub with galleries and museums that reflect the sanctity of both political and religious institutions in the nation’s founding and future (e.g., the Smithsonian Institution, the Museum of the Bible). Today, as in the past, Washington houses many of the artefacts and institutions that establish rule: of God over the people, of the “United States” over the land, and of the people over the futures they envision. This understanding of God’s governance over the land, its people, and its public spaces is not limited to D.C., however, nor does it go unchallenged — which is particularly evident in the traffic between theology and sovereignty that this project explores. So, in moving across the land by car, crossing the border between Canada and the United States, this project approaches the capital as a web of meaningful connections that fan out across the North American continent and come together at this specific site. Layered with the writing such movement made possible, a road trip and the creation of map provide productive means for reckoning with the competing voices that lay claim to highway infrastructures, farmland, city blocks, and even the air space through which the research team traveled.

This multimedia project draws on Hent de Vries’ introduction to the volume Religion and Media (2001) to help foreground the interdependence of secular and sacred media in public spaces. Such theories also inform the team’s own use of audio-visual media as ethnographic entry point for understanding new and old forms of authority in documenting national history and religious identity, whether in museums, on the roadside, or in scholarship. Throughout the project, the contributors asked how the infrastructures of religious identity and affiliation appear amongst and in the form of purportedly “secular institutions” that are dedicated to the political history and national identity of America more broadly, while also considering how they depart from these cultural models these institutions put forward.

The visual story that the logic of a map tells foregrounds the geographic proximity of these sites and the potential influence they might have on one another — the cultural significance of the national mall, for example, endows the placement of new institutions of display in that area (such as the Museum of the Bible) with a certain authority, meaning, importance. By including photos and written descriptions to pinned locations on a map, the similarities and differences between such institutions can be seen more clearly, as visual documentation makes it possible to compare architectural or exhibition designs, among other details.

Part II:

The Research Team

Suzanne van Geuns is a PhD Candidate in the Department for the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto. Her research examines online instructions for how to be a man or woman in the right way, from biblical womanhood bloggers to ‘seduction’ forums for men. She is broadly interested in American conservatism, focusing on the internet as a place where truths that gender essentialists of various stripes consider uncomplicated and eternal are affirmed, explained, and put to practice. In addition to knowing way too much about strange corners of the internet, Suzanne enjoys trying foods that are so spicy she will cry, going out to dance, and peanut butter cups – truly one of America’s greatest gifts to the world.

Kyle Byron is a PhD student in the Department for the Study of Religion at the University of Toronto. His research, grounded in the ethnographic study of street preaching in North America, examines the everyday labor of religious revival, focusing on how the promise of revival structures Christian life in the present. When he wants a break from reading and writing, Kyle enjoys rock climbing, eating raw cauliflower, and taking photos of his very cute cat, Pippin.

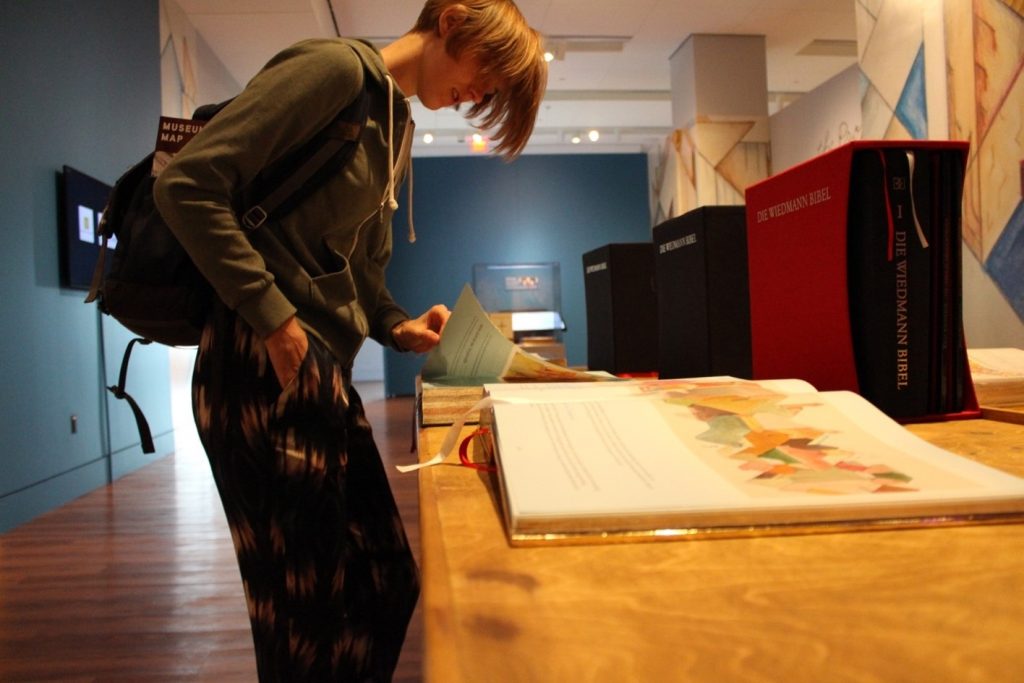

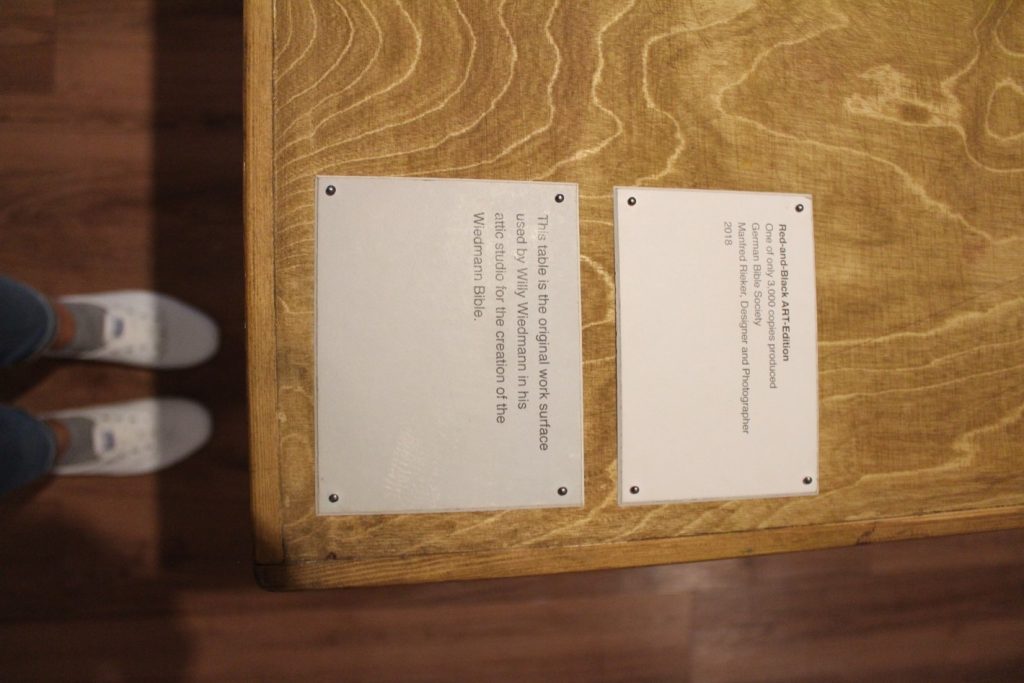

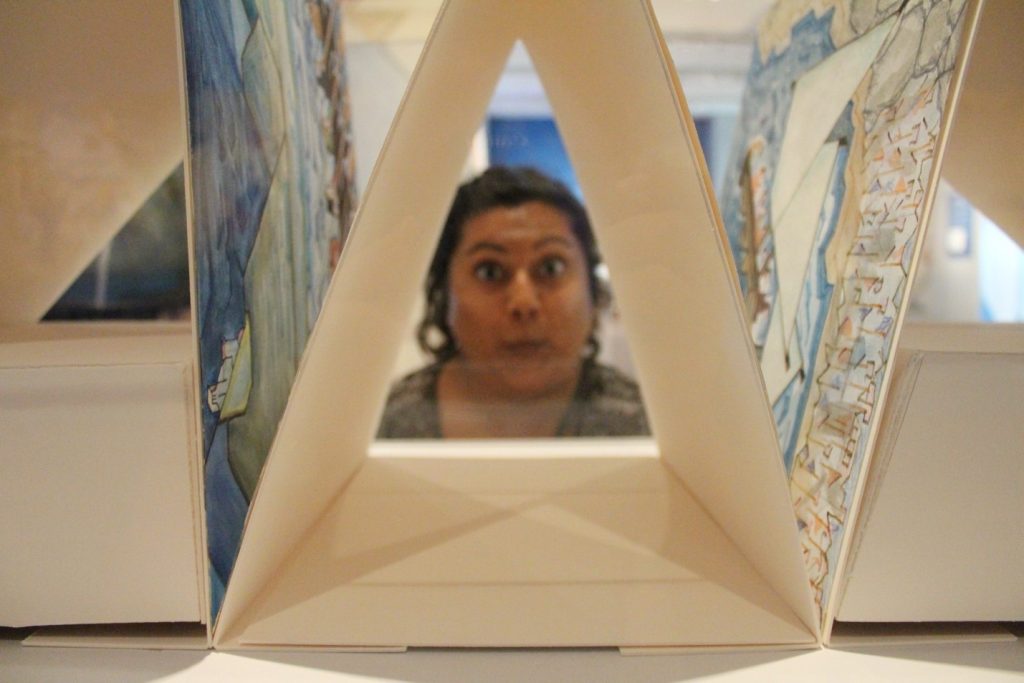

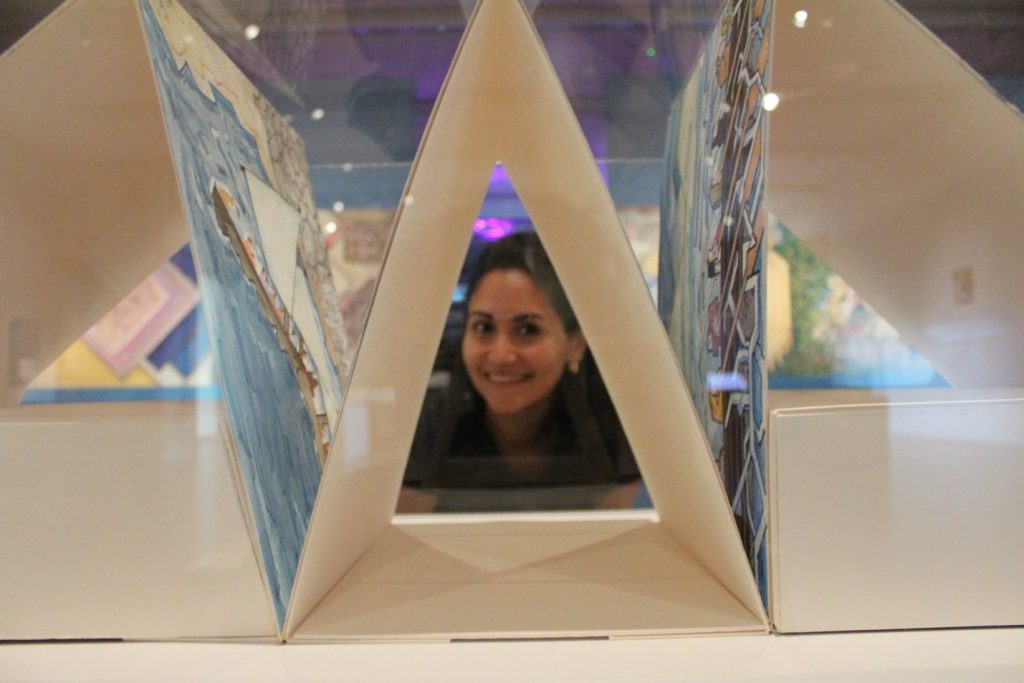

Christina E. Pasqua is a PhD Candidate in the Department for the Study of Religion and the Book History and Print Culture program at the University of Toronto. Her dissertation explores the politics of Bible translation, particularly how Christian publishing companies have embraced the semiotic codes and conventions of the comic book industry to disseminate the Bible as a visual text. Autumn is by far her favourite season, but her love for house plants, coffee, and chihuahuas persists year-round.

Saliha Chattoo is a PhD Candidate at the University of Toronto’s Department for the Study of Religion and a freelance food and entertainment writer in the city of Toronto. Her doctoral research looks at Pentecostal youth in Texas and the ways in which they negotiate their political and religious identities in performance-based conversion and ministry spaces. Saliha loves road trips, hates raw cauliflower, and never measures the amount of coffee that goes into her french press so that every day is an adventure.

Part III:

Why a Map? A Note from the Research Team

Prior to our departure, the team discussed many different options for how we would share our research findings — from photo essays to a podcast series. In the end, we decided on a map.

The map serves as a kind of audio-visual ethnography that documents our research road trip from multiple subjective and multimedia perspectives. As such, the map is not only a means for us to display our findings—or “raw” data (e.g., a photograph of the Museum of the Bible serving as visual evidence of its existence)—but is also a medium through which we can reflect on the process behind how we got to each site and what we saw along the way. The map’s contents therefore offer some perspective on who we are as researchers, citizens, museumgoers, and friends. Put differently, the map is a testament to the kind of “deep hanging out” that we engaged in, the kind work that Clifford Geertz suggests ethnographers do; it is a testament of our specific research process, whether at the sites themselves or during the “behind the scenes” moments that enabled us to think about and respond to the central questions raised by the larger Entangled Worlds project: “how and why do attachments to soil matter?”

The pins on our map only begin to provide some answers to these questions, primarily through photography and written reflections that make such cartography possible (along with Google Maps). It is important to remember, however, as Jonathan Z. Smith writes, that “map is not territory.” As such, our map is a construct and it is inhabited by our particular perspective. This perspective is layered onto an international map whose bounds may or may not be fully recognized by many various sovereign powers who also construct and maintain their own maps by inhabiting the spaces through which we traveled. In other words, the map traces our activity at very particular times and places that you may now interact with at your leisure.

The geographic area covered by our research trip is quite large, so the map is best navigated in sections — i.e., zoom in and click on one of many “green” coloured pins for more detail. For easier and more direct access to specific sites, you will find the title of each pin listed in the side bar on the left side of the window. As you navigate the map, you will see that each pin includes a selection of photographs taken and curated by Kyle Byron and Christina Pasqua (with a few photos from Saliha Chattoo) and brief descriptions of our adventures, general observations, and historical context written by Suzanne van Geuns (with a few entries written and edited by Christina Pasqua).

Some of the sites we visited were quite large (e.g., the Ark Encounter in Williamstown, KY), so we decided to include more than one pin for such grand displays of sovereignty and sanctity in North America. Doing so allowed us to provide a more layered perspective of the size, scale, and experience of these infrastructures and the soil on which they were built. The Ark Encounter, for example, has six separate pins, so you will need to closely zoom in on the map to fully access our documentation of it. The same goes for the Museum of the Bible, which has four separate pins that are thematically organized. A few pins on the map also include videos (e.g., click the title “Noah’s Ark: Exterior,” where you will find a video recorded by Saliha Chattoo while she conducted a pre-interview with the research team before entering the Ark Encounter).

If you have any questions as you navigate the map or if you see corrections that need to be made, please feel free to contact us. For optimal access, we suggest using Google Chrome as your browser.

And now, we present you with a visual tour of our research project:

Part IV:

Ethnographic Vignettes

In addition to the map, each member of the research team also wrote individual responses to the research road trip that are included here as ethnographic vignettes. Christina, Suzanne, and Kyle present their work as photo essays whereas Saliha’s piece is built around her transcription and curation of recorded conversations had at various points during our travels.

I.

Visual Ethnography as Testimony of “Deep Hanging Out”

by Christina E. Pasqua

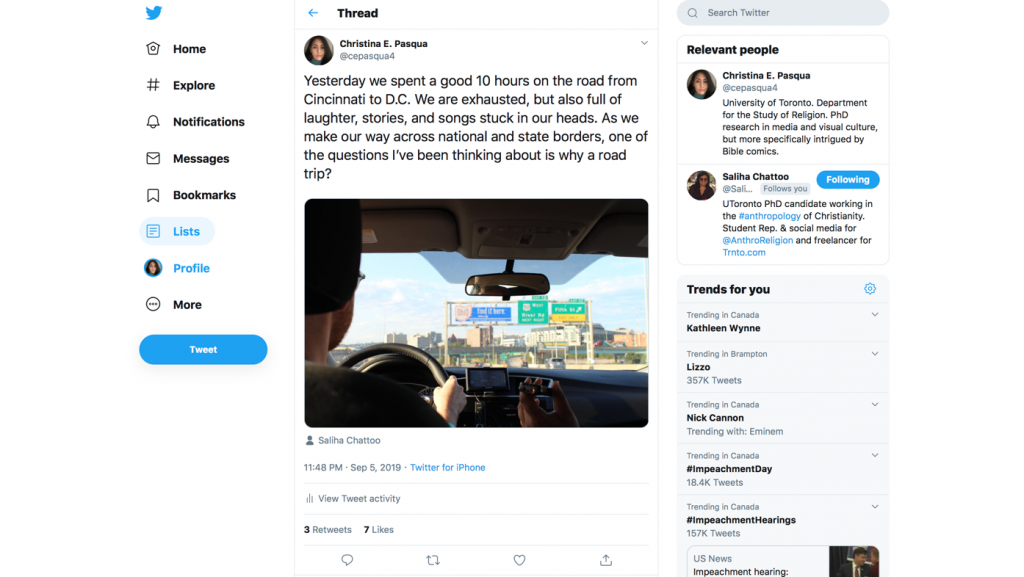

The best part of the trip, as I reflect back on it now, has much to do with the process of documenting it: our interactions with one another and the places we visited as we closely read and photographed signs, exhibits, and observed the people who filled the space. I chose to document the project primarily through photography and writing during the trip and through photo curation and video editing afterward. Each step in the process has allowed me to tell our multicentred research story from my own perspective and creative lens. Take this Twitter thread for example:

The Tweet is framed by our collective experience of being on the road together as well as the many conversations we had in and around the car, but the narrative is told through my voice as author and my line of vision as photographer. The latter, in this case, is dependent upon my position in the car insofar as this could yield different kinds of photographs. In the above, I see Kyle driving us back to Cincinnati while Saliha records our conversation from the passenger seat. I am in the back seat of the car with Suus to my right. Here, we are debriefing thoughts, questions, and concerns raised after visiting Ark Encounter, the Answers in Genesis Creationist theme park. In visually documenting these moments, we gain a better sense of what Clifford Geertz meant by “deep hanging out.”

Research happens on site, but also in the spaces between. As anthropologists, we were not limited to the physical infrastructures of the universities in which we work nor the museums we visited because this project became a process of “total immersion.”

Our writing happened online, in Google Docs files and emails chains. Our thinking happened as we ate lunch off a turn pike or while Kyle filled the car with gas, and now our map and your interaction with it includes you, as reader, in this process.

These in between moments are, as Matthew Engelke argues, “the crux of hanging out” because these moments are “about what you can observe with someone at an art museum when you meet [them] not to conduct an interview … but just to spend time to get to know one another” (2013, xxvi). For me, “hanging out” is also deeply connected to Roger Canals’s understanding of visual anthropology, where what you see, what you do, and how you think in relation to others — a research process typically conveyed in edited words — is made visible.

Hanging out with other anthropologists reveals how we see the same things differently, while together, and how these differences are reflected in our distinct practices of writing, reading, speaking, listening, and, seeing; something that our map, these vignettes, and the following photographs uniquely convey, each in their own way.

II.

Performing American Christianity, Performing Legitimacy:

Reflections on Ark Encounter

by Saliha Chattoo

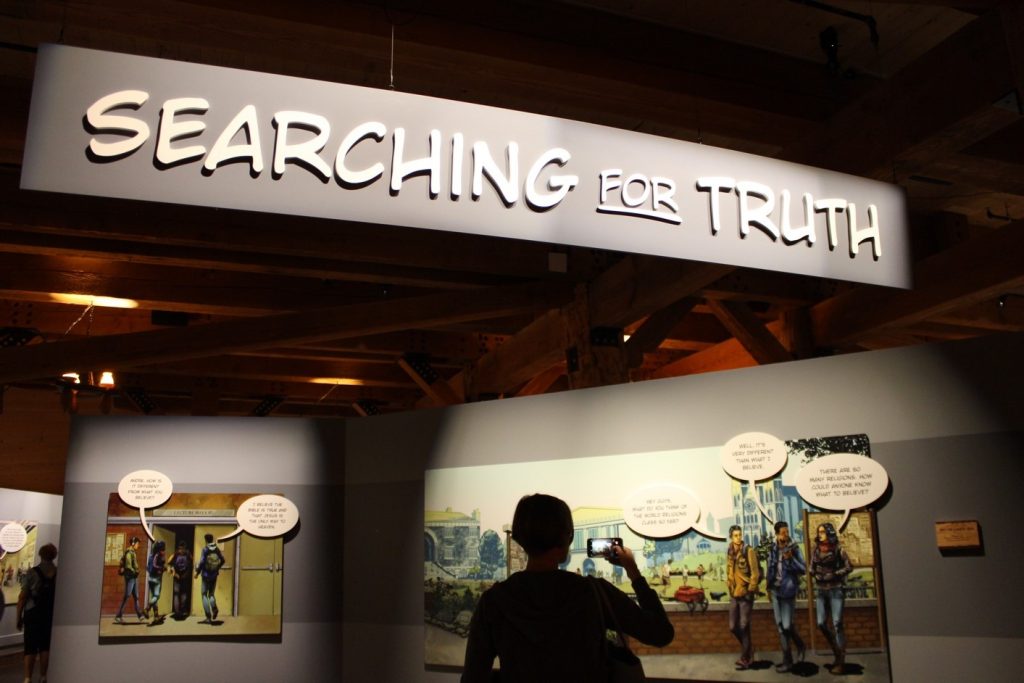

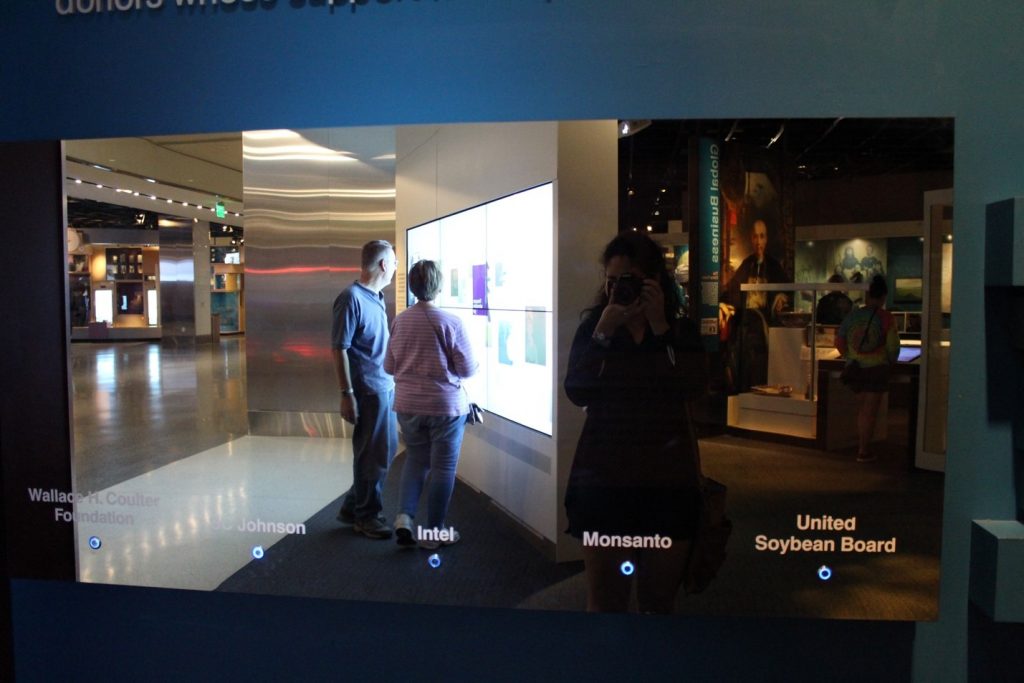

When Answers in Genesis (AiG) opened the Creation Museum in 2007, one of their main advertorial messages was that it would be a museum with biblically informed exhibits that could compete—in terms of production values, resources, and presentation—with science and natural history museums that teach evolution. We know from consuming art and entertainment more broadly that there is a type of persuasion and legitimacy that can be signaled via quality aesthetics. But what are the other ways in which legitimacy, history, and authenticity are signaled in these spaces? This is a question of the politics of persuasion as much as it is a question of the aesthetics of immersion.

AiG’s Ark Encounter is part theme park/Sunday school/museum, deliberately pulling from all three as archetypes for its exhibit design in order to perform different but equally important modes of authenticity. What is it that other sites of display like natural history museums are doing that might be seen as valuable or worthy of imitation? How might AiG have translated those efforts onto similar mediums to achieve their own didactic goals?

As we consider AiG’s projects within our broader questions about the ways in which these spaces craft narratives of America, Christianity, power, and sovereignty, we might also consider how the medium (the museum) is modeled to be persuasive (Bielo 2015).

One of the ways in which Ark Encounter performs authenticity is by setting certain materials apart—behind ropes, under glass, in display cases. But what they often choose to set apart, in a way that signals value or historical significance, were the same reproductions that appeared elsewhere in the space. Wheelbarrows hauling bags of plastic olives rested next to an encased imitation of a typical meal (bread, olives): one open to the touch, one decidedly not. The museum model is tightly connected with the material: making history and ideology immanent through the display and discussion of material culture. The project of Ark Encounter itself is to bring stories into the realm of the tangible so that families, schoolchildren, and tourists can learn from seeing, touching, hearing, and smelling. Soundscapes of water and animal activity combined with the smells of food and waste as patrons walked by clay pots, burlap bags, and wooden crates they could run their fingers over. The reification of Bible stories into the material is the very point of it all.

Suzanne: “It’s embodied apologetics”

Saliha: “Exactly. And Ken Ham was attentive to this in his talk today. He said youth are asking questions in Sunday school, and the pastors are answering with just trust in Jesus, just trust in Jesus. [Ham said:] ‘we’re trying to just make our kids obey but we need to give them answers.’ So in a way it’s is a very smart idea if you’re trying to attend to the ‘already gone’ issue (title of Ham et al.’s 2009 book). The ‘how do we keep youth in the church questions.’ It’s actually practical whereas usually when churches ask ‘how do we keep the youth,’ the whole day of the conference is really just like ‘oh those youth…” and there are no concrete solutions offered. This is a concrete solution: let’s do apologetics, let’s give them some answers. So that when they get to school, [especially if they go to liberal universities] or they’re talking to somebody out in the world, they have the language to say something.”

Christina: “One thing that really struck me [in a video presentation of the making of Ark Encounter] was how they were talking about the potential for spotting that [an animal is] a fake. So they said we start with a lot of hair but we have to cut it down in just the right way. Or we’re layering on multiple patches of hair that we kind of have to blend together and make it look more realistic. That illusion and thinking about the mechanics of artistic work and that these animals are not just objects that you look at but there’s an intent and a very careful action behind how they’re designed. I thought that was really incredible to see and to hear that perspective because it’s really easy to take everything for granted. I think I even asked [Bielo] before I saw the video, were these created externally and then brought in, because there’s so many of them. It is a lot of labour. And then you see the people behind the design [in the video] saying no, we did this, we punched every single hair on this boar [by hand with a needle]. It gives life to that process. You don’t hear too much about that side of things. It’s usually all about the content or the argument, the rhetoric. To hear the material side of it, that’s what makes this experience possible.”

…

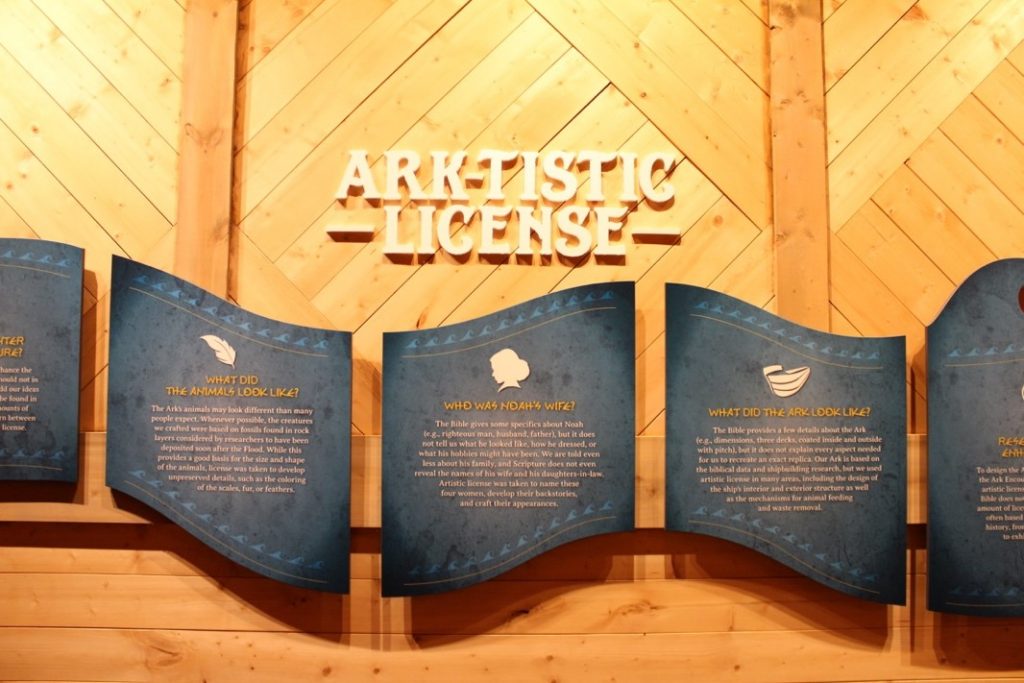

Saliha: “The attention to detail was very impressive. And I noticed on many plaques, discussions about any creative licenses taken [in trying to bring the Ark alive like this]. I think those plaques were anticipatory and defensive too. They were like ‘I don’t want you to get hung up on a thing that was part of our creative license and then you don’t believe.’”

James: “Especially the very first [plaque]. That was added, that wasn’t there the first couple of times I went. I think it was like the third time I went, it appeared. My initial thought was: I don’t think the [creative] team is happy about this. Because it breaks the immersion. And before you even get the immersion going. So yes, it’s absolutely anticipatory. They’re building in signs to speak back.”

[This is re: signage that explains how AiG is going beyond the biblical account]

Especially in the case of Ark Encounter but also in the Museum of the Bible, material culture is relied on to perform history, and by extension, authenticity, but of course the materials in question aren’t always the type to be preserved in the archaeological record. At Ark Encounter, it’s impossible to showcase an artifact as the category is traditionally understood (i.e. the actual preserved object). Instead, things like loaves of bread, olives, wooden animal cages, etc., are simulated via new materials. What’s notable is that the same recreations that proliferate throughout the space are sometimes set apart from others in order to perform historical material culture. For example, at Ark Encounter (and even in some cases at the Museum of the Bible), things like plastic loaves of bread and other material aspects of daily life were encased in glass or given an explanatory plaque where a discussion of its suggested role in history would be explored. While no one would assume the bread they see displayed under glass was in fact from thousands of years ago, I noticed a particular performance of authority, legitimacy, and history in the technologies of display.

Saliha: “In the case of the creation museum,[1] [there’s a modeling of] natural history museums. Some of the initial ideas for the creation museum Ken Ham had were: ‘what about our kids? Where do they go? They’re going to these natural history museums and they’re being corrupted because of the information but also because of the performance value of these places. This is what James talks about in [his book] Ark Encounter. Being aesthetically persuasive is important in these projects of publicity. The aesthetics of persuasion: it matters. And James’ interlocutors talk about how they wouldn’t bring visitors if they thought it was embarrassing.”

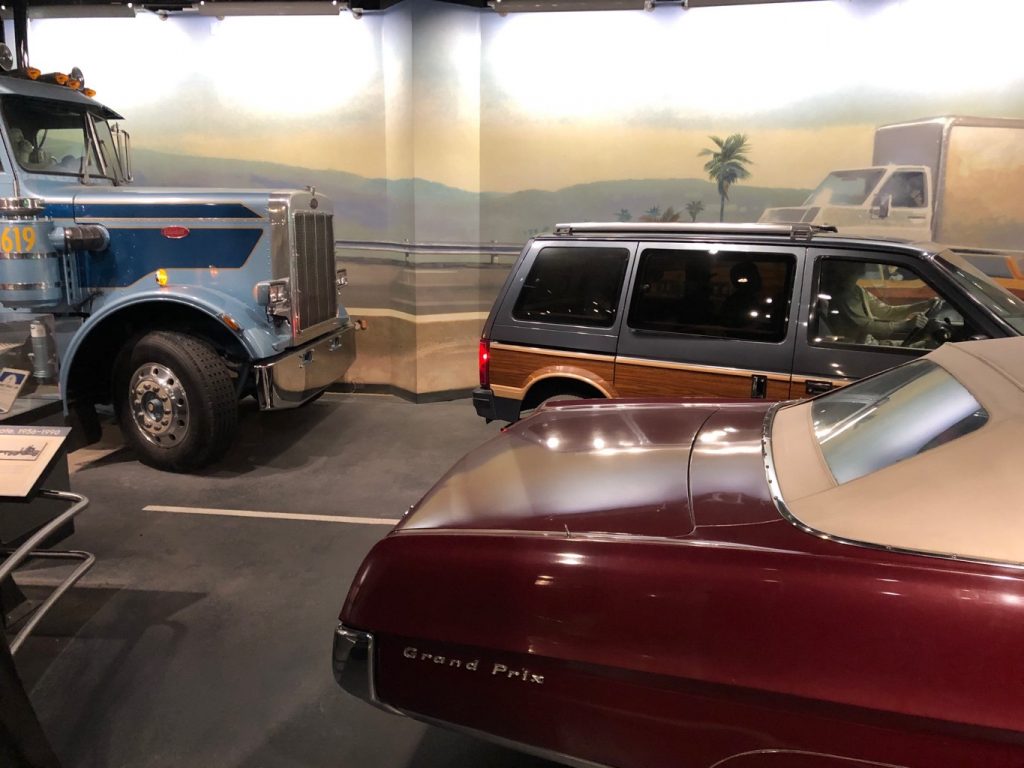

Sara: “From my perspective going to the museum and going to the ark, they’re doing similar things but they’re using different tools of modernity to do it. [The Creation Museum is] trying to mimic a natural history museum, to the point where you walk in and they have a skeleton of a dinosaur. That’s the classic entrance to a natural history museum. The Peabody museum at Yale, you walk in, and there’s a skeleton of a dinosaur. So that triggers a response where you automatically trust as scientific knowledge what you’re going to imbibe in this museum. Because it is this fact-based experience, this historical experience.

As opposed to the Ark, from the moment we got there, it invoked the movie Jurassic Park to me. To the point where I was like we have to watch this tonight. It felt much more like theme-park-ish. Like I’m going to Disney world. Not the magic kingdom, but animal kingdom. Like oh, I wonder if they’re going to have a roller coaster here. Whereas I never would have anticipated a possible roller coaster at the creation museum. So, I feel like they’re using different tools of modernity to immerse you in different ways.”

The Creation Museum and Ark Encounter were opened nearly a decade apart from one another (2007 and 2016, respectively), and although they technically reside in different states (Kentucky and Ohio, respectively) they are a mere 45-minute drive from one another. As we consider the theme of infrastructures of religio-political identities and affiliations it’s important to think about the politics behind decisions of where to plant these projects of publicity, education, and American and/or Christian identity (re)construction.

Saliha: “I like thinking about borders here. At lunch [at the Ark Encounter] Suus had a moment of “where are we, again? Is this Ohio?” And it’s perfect because these Answers in Genesis spaces are positioned between and over state borders. Now that they have the sister projects that are relatively close together, you could almost redraw this new line instead of state lines: AiG space. It’s now this kind of pilgrimage site that families are coming to. AiG has built this place where you can go back in time, but also a place you can go to a museum that teaches [biblically-informed histories].”

Suus: “They thought about why to put it here. —Is this an area where people are homeschooling a lot, is this a very fundamentalist area in that sense? Or are people just making the trek here?”

Sara: “Well, Kentucky at least, and southern Ohio/Kentucky sort of bleed into each other to the point where there are a couple of different towns in northern Kentucky that are basically neighbourhoods of Cincinnati. Kentucky is squarely in the Bible Belt but it’s sort of in the northern part of the Bible Belt. It’s sort of in a central location where it’s kind of accessible to [people, say, in Buffalo]. It was a doable drive to drive down, because it wasn’t way down in Alabama or somewhere deep in the South. But if you lived in the deep South, it would still be pretty accessible.”

James: “That was part of the founding rationale. Less than a 12-hour drive for two-thirds of the American population. Anecdotally there was a homeschool conference in downtown Cincinnati, and that’s not incidental.”

Kyle: “One of the questions we want to think about is what’s the relationship between Christianity and sovereignty in Kentucky and then Christianity and sovereignty in Washington, D.C. and how are those different in these two museums [Ark Encounter and Museum of the Bible]. Because they’re two very different kinds of places to think about Christian power. And the meaning of sovereignty is probably way different in the capital of the country than in like a more conservative slightly more nationalist non-capital place.”

[1] Here, Saliha is referencing two of her previous field visits to the AiG Creation Museum in Petersburg, KY in 2011 and 2015.

III.

by Suzanne van Geuns

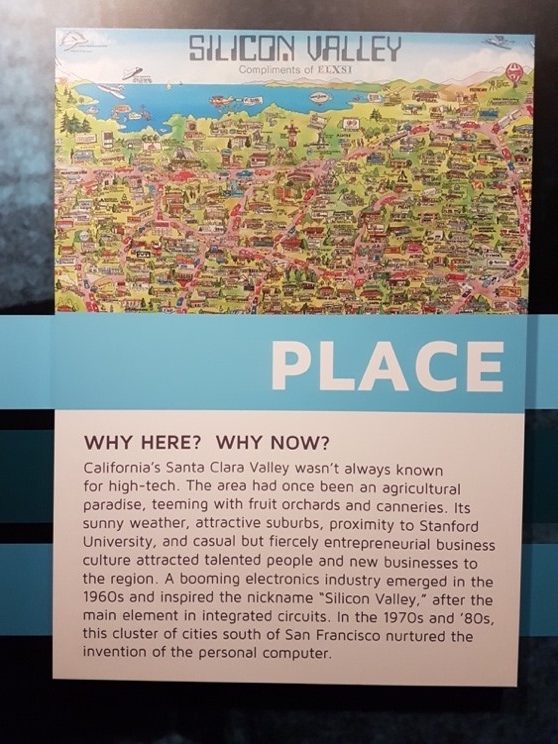

An abiding story the United States tells about itself is that it is a nation of inventors. Big tech companies today legitimate their sovereignty with reference to their innovative strength, a move that also finds its way to the museums we visited. In the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, a stroll across the ground floor leads from the exhibit about Edison into the story of how the same Californian region that held his copper-wire innovations became Silicon Valley.

From the telephone switchboard to the ethernet circuit, the ‘wizards of Menlo Park’ have lorded over American inventiveness as if over a religion. But crossing the street to the Smithsonian Museum of African American History, inventiveness presented itself differently: instead of America rising ‘because of’ invention, here its inhabitants invented ‘in spite of’ the nation’s sovereignty over them.

Throughout our trip, we saw creativity of many kinds: from light bulbs or electronic switchboards in glass cases to street art and pastoral support that can be dialed on the road. Moving across the land, whether driving along the highway or crossing into a different museum, helped the powerful claims to sovereignty innovative ‘wizards’ or inventive artists put forward fit alongside each other anew. Their work blurred into a kaleidoscopic picture of presence and the accompanying effort to make it persist. This is what roadside signs announcing that Jesus died for us have in common with Silicon Valley optimism about the ability of electronic chips to reorganize our existence: they tell us who’s here, and who matters.

IV.

Ark Encounter: Geological Evidence of God’s Sovereignty

by Kyle Byron

As we approach the ark, we walked past a series of weathered stone tablets describing key event in the book of Genesis. The relationships among God, humanity, and the earth figured prominently on the tablets. For example, the third tablet—following tablets portraying the creation and fall of man—included a relief of Eve, pregnant with a child, and Adam, laboring in a field. A sign accompanying the tablet explained, “There would be pain in childbearing, and God cursed the ground, making man’s work difficult.” After two more tablets describing the murder of Abel and the “vile behavior” that subsequently filled the earth, the final tablet showed Noah looking on as the flood waters physically separate the righteous and the wicked. The people and animals killed by the flood were represented as skulls neatly aligned in three distinct layers of earth. An apparently small detail, these three layers of earth form the foundation of Ark Encounter’s claim to Christian sovereignty. Rather than describing sovereignty in the language or nationalist romanticism, states and their borders, or even—surprisingly—divine command, the museum presents a distinctly geologic understanding of sovereignty—that is, a claim to dominion rooted not in the soil, per se, but in rock layers, dating techniques, the movements of continents, and all of the abstractions that allow geologists to do the things they do with the earth.

The geological evidence of God’s sovereignty features most prominently in an exhibit titled “The Flood: What Happened Outside the Ark.” Departing from the moral language of the righteous and the wicked, the exhibit explains what happened to the earth—physically—during the flood. For example, one illuminated display features an image of water rushing through a canyon, explaining that when the flood waters receded as a result of God’s direct manipulation of the earth, “large amounts of sediment [were] washed away and canyons [were] quickly carved into the rock layers.” The next display features a scientific diagram of tectonic plates shifting, “The relatively swift-moving continental fragments (plates) collide underwater forcing up mountain ranges. Today’s mountains filled with marine fossils bear evidence of this event.” Another even offers a geological explanation of the rain that occurred during the flood, noting that when magma came into contact with seawater, stream jets would “shoot through the ocean and into the upper atmosphere generating intensely heavy global rainfall for 40 day and nights.”

Moving through this exhibit, I eventually came to a room focused on the creation of fossils, a common point of contention between Young Earth Creationists and the mainstream scientific community. The displays explained how a process of “rapid burial” produced fossils and organized them neatly into rock layers, all in a relatively short period of time. As I approached a case containing fossils organized beside a chart describing seventeen distinct layers of rock, I stopped next to a man and woman who were already standing silently in front of the display, almost reverently.

After a few moments, the man took a step toward the display and pointed vaguely toward it, moving his finger up and down along the names of the rock layers, “See? Cretaceous, Jurassic, Cambrian… There it is, there it all is. I mean… See it?” The woman responded with noticeably less enthusiasm—even a bit of skepticism—“Mhmm…” I couldn’t tell if she was genuinely unconvinced, or if she was tired of having each display explained to her as she looked at it, or if, like me, she was simply exhausted after spending all day in the museum. They stood silently for a few more moments, then walked side by side to the next room. As I reflected on the way that soil figures in Ark Encounter, I would often replay this moment in my head, “There it is, there it all is.” The man spoke with a tone of relief, almost as if he was trying to convince himself as much as the woman he was with. After wandering through an intricately crafted and immersive life-size replica of Noah’s Ark, the list of rock layers in the display seemed, to me, hardly noteworthy. However, for at least one visitor, there it all was.

In Ark Encounter, soil is often positioned against water, the former associated with sin and the latter associated with punishment and, in turn, purity. However, it was only after I returned to my photographs several weeks after the trip that I began to notice the subtle yet consistent role of geology in the museum, long before it became an explicit theme in “The Flood: What Happened Outside the Ark” (for example, in the visual harmony between the layering of bones in the stone tablet describing the flood and the scientific diagram describing rapid fossilization). It is striking that, among the many ways the term soil has been invoked in our conversations about the entangled worlds of sovereignty, sanctity, and soil, the science of soil has been largely absent. However, as Marjorie Hope Nicolson points out in Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory: The Development of the Aesthetics of the Infinite, geologists have been using soil to stir up aesthetic, political, and theological trouble since at least the 17th century, when sin—not tectonic plates—explained the jagged contours of the earth’s mountains and valleys.

Part V:

References

Bielo, James. “Literally Creative: Intertextual Gaps and Artistic Agency.” In Scripturalizing the Human: The Written as the Political, edited by V. Wimbush, 20-33. New York, NY: Routledge, 2015.

Engelke, Matthew. God’s Agents: Biblical Publicity in Contemporary England. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2013.

Geertz, Clifford. “Deep Hanging Out.” The New York Review of Books. October 22, 1998. https://www.nybooks.com/articles/1998/10/22/deep-hanging-out/

Ham, Ken, Britt Beemer, and Todd Hillard. Already Gone: Why Your Kids Will Quit Church and What You Can Do to Stop It. Green Forest, AR: Master Books, 2009.

Nicolson, Marjorie Hope. Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory: The Development of the Aesthetics of the Infinite. Seattle: University of Washington Press, [1959] 1997.

Smith, Jonathan Z. Map Is Not Territory: Studies in the History of Religions. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1978.