Photographing the Holy Land: A Visual Exploration of “Sovereignty”, “Sanctities” and “Soil” amongst Orthodox Jews in Jerusalem, Palestinian Israelis in the Galilee and Palestinian Christians in Bethlehem

Hannah Mayne, Marianna Reis and Connie Gagliardi

The specificity of the visual as a medium lies in its ability to convey and make known that which is not possible through other mediums. Using three sets of three images for each of the communities this project is focused on (Orthodox Jews in Jerusalem, Palestinian citizens of Israel in the Galilee and Palestinian Christians in Bethlehem), this project uses images to reveal the theopolitical nature of sovereignty; to demonstrate the role of religion in expressing “good” and “bad” forms of public and civic life; and to affectively capture the politics of sensing the divine within and amongst such different social communities. The fact that these three loosely-defined groups all share the same landscape – that of the Holy Land, albeit with their own individual names and designations for such landscape, or “soil” – gives this visual ethnographic project a potent basis for comparison. Images here function as a mode of writing and representation.

At the same time, Dr. Roger Canals Vilageliu has written about the image as “an ethnographic research method” (2010). In his analysis of the image in the cult of Maria Lionza in Venezuela and amongst Venezuelan migrants in Spain, Canals Vilageliu ethnographically likened his camera to a “mirror”, revealing particular affects and understandings of the gaze, divine immanence and political potentiality. Fieldwork experience with the camera has the potential to invite the ethnographer into a wider scheme of “visual affordances” that operate in each context, the “specific cultural and social milieu” from which they emerge (2018: 169).

These images are the result of such an ethnographic encounter, and as such they reveal a deeper cultural and social, but also religious and political, theopolitical milieu that is better captured in image than rendered in text.

However, images are also objects. They have a material quality to them that is both sensuous and evocative. They are social agents, capable of provoking viewers, whether it is through poignant absence, sensuous immediacy, or auratic possibility. Indeed, in W.J.T. Mitchell’s What Do Pictures Want? (University of Chicago Press, 2004), he writes, “A picture is a very peculiar and paradoxical creature, both concrete and abstract, both a specific thing and symbolic form that embraces a totality…To get the picture is to get a comprehensive, global view of a situation, yet it is also to take a snapshot of a specific moment – whether it is a cliché or a stereotype, the institution of a system, or the opening of a poetic world” (2004: xi).

This project presents a total of 21 images from 3 different places in Israel/Palestine, in the hopes that it will help viewers “get the picture” of the Entangled Worlds of the Holy Land.

But, what does it mean to “see” in the Holy Land?

The social gaze and the act of seeing is politicized within and amongst the three groups analyzed in these images. This comparative project thus pushes the limits of seeing in the Holy Land by situating these image sets of such different communities living upon the same “soil” together, in disparate but similar ways – perhaps opening up a poetic world adept to theopolitical revelation at the same time.

Orthodox Jews in Jerusalem

Series I:

There is a biblical commandment on the Jewish holiday of Sukkot to ritually hold and shake together a citrus fruit (interpreted as the fruit of the citron tree), a palm frond, boughs from a leafy tree (interpreted as myrtle), and willow branches. In contemporary orthodox communities, each adult male must own a set of these four plants.

The market for these items comprises an international industry around the time of Sukkot (September or October) each year. According to rabbinic interpretation, there are strict and complex rules for exactly how to assess the quality of each fruit and branch – which must not show any blemish in order to be considered kosher for ritual purposes. It is not unusual therefore, for those purchasing these items, to meticulously inspect each and every millimeter, and to invest large sums of money in order to acquire the most flawless products. Consequently, in order to protect the fruit and branches, they are generally wrapped in layers of foam, plastic, or cardboard.

The three photographs in this series were taken at one of the biggest markets in Jerusalem. I aimed to capture how these plant items from the soil are transformed into sacred objects through commercial relationships, rabbinic rules of material aesthetics, and men’s practices of inspection and scrutiny.

Series II:

These three images were taken at a mass orthodox women’s gathering to pray for single women, that they will soon marry.

The event took place at the sacred site of Rachel’s Tomb, in the Israeli-occupied West Bank. The organizer distributed a short compendium of liturgical texts, which the hundreds of women who were present uttered out loud together. In the middle of the prayers, Rabbanit Yemima Mizrachi, a major female religious personality in contemporary Israeli society, arrived to lead the women in another set of petitional recitations, which she inter-weaved with short, inspirational sermons. She then publically performed a dough-separating ceremony – a practice that Jewish women traditionally carry out in their kitchens when they bake bread, but that, in recent years, has become the focal point of large women’s prayer meetings. According to Jewish custom, dough-separating is one of the three primary rituals that are associated with women and that protect them from dying in childbirth.

The first photograph shows the discarded bags of wheat flour, the sandwich bag that held the yeast, and the disposable cups that were used to pour water into the dough mixture. I found these plastics on the gravel road a few meters from the event. In the second photograph, Rabbanit Yemima is holding in her fist and saying the prayers over the lump of dough that was symbolically removed from the mixture in the main bowl. The third picture shows the narrow street crowded with women attending this special event, the partitioned men and women’s entrances to Rachel’s Tomb on the left, the tall, concrete separation wall that separates the sacred site from Palestinian Bethlehem on the right,

and the Israeli military towers and cameras in the background.

and the Israeli military towers and cameras in the background.

Series III:

These three images are taken in the Old City of Jerusalem.

The first depicts the overflow of notes, addressed to God, which were piled-up on the stone floor on the women’s side of the Western Wall during the auspicious month of Elul, the month of prayer and repentance before the Jewish New Year.

The second image, also from the women’s section at the Western Wall, was taken moments after a group of approximately ten women had completed their communal morning service, having sat in the chairs in the center of the photograph. In contrast with the much larger feminist group, the Women of the Wall, which is at the center of media attention and public debate in Israel and the Jewish diaspora, the women in this small break-away group, Original Women of the Wall, in their words, “come, pray, and go home.”

I took the third picture at dawn, looking down towards the Palestinian neighbourhood of Silwan. The blue lit-up stars have been erected by Jewish settlers on the roofs of their homes – a kind of occupation of the visual landscape, especially noticeable during the night, that sets out to compete with the green lit-up Muslim crescent moons erected on top of Palestinian buildings.

Palestinian Israelis in the Galilee

Series I:

The first photo depicts an iftar—the breaking of the Ramadan fast—on a farm in Wadi Ara, a region of Northern Israel with a high concentration of Palestinian citizens of Israel, hosted by the farmowner and attended by members of a local activist youth group. He led us on a tour of his property and the surrounding forest, stopping at the gravestones of his ancestors and narrating the rolling hills all the way back to the Canaanite era. After an hour of hiking in the relentlessly hot and stick late-May air—which rendered many of the fasting youth weak and faint—we returned to the courtyard to break the fast together.

Several structures on the farm, including family homes, sat demolished near the courtyard where we ate our iftar meal. The farm owner currently faces additional demolition and land confiscation orders from five different state entities. He told the group that he recently offered to exchange his land, comprising 62,000 square metres, for 60 square metres of Mount Zion in Jerusalem, to make the point that his land “is as holy and sacred as theirs”.

Series II:

This is a cross-section of the Lower Galilee: to the centre-right is Mount Tabor, the alleged site of the Transfiguration of Jesus. It is administered by Keren Kayameth LeIsrael – Jewish National Fund (KKL-JNF), an organization founded in 1901 on the principle of purchasing and developing land in historic Palestine for Jewish settlement. The Arab town of Daburiyya sits at the foot of the mountain and further in the foreground is the town of Iksal; both survived the Nakba. To the left is a neighborhood in Nof HaGalil (previously named Nazareth Illit), a Jewish town built in the 1950s as part of the state’s “Judaization” efforts to increase the Jewish population in the Arab-majority Galilee. I took this photo while standing on the side of a garbage-filled road atop Mount Precipice on Nazareth’s southern edge—the site where an angry mob attempted to run Jesus off the mountain after he claimed to be the Messiah, according to the New Testament. Mount Precipice also administered by KKL-JNF. The differences between Nof HaGalil –formally planned, spacious, clean, well-maintained – and the surrounding Arab localities – unplanned, dense, in disrepair – are visible even at a distance.

This amphitheater, built to accommodate Pope Benedict XVI’s 2009 visit to Nazareth, sits on Mount Precipice against the backdrop of Nazareth’s overcrowded urban landscape. It sat vacant until June 2019 when Nigerian televangelist TB Joshua held a two-day televised event that attracted pilgrims from around the world to witness his purported divine healing miracles. The fissures dividing Nazareth along intertwined class, ethno-religious, and political lines, were momentarily set aside as the city’s residents, religious leaders, and political figures demanded the event’s cancellation, on the grounds that the entanglement of Joshua’s apocalyptic interpretation of the Bible with his ties to far-right pro-settlement Israeli figures, is harmful to Palestinians.

The white sail-like structure and the brown complex next to it comprise Big Fashion, Nazareth’s premier shopping mall. As a number of Nazarenes bitterly explained to me, the mall sits on land owned by the Greek Orthodox Church, which has significant land holdings across Israel-Palestine; in recent years, sales of Church lands to pro-Israel entities, including settler organizations have drawn the ire of Christian and Muslim Palestinians, with the former expressing concern about shrinking Christian space in the Holy Land. Furthermore, one of the mall’s co-owners is Africa-Israel Ltd., a company owned by diamond mining magnate and businessman Lev Leviev, who is involved in constructing illegal West Bank settlements.

Series III:

This is a small sliver of the ruins of the destroyed Palestinian village of Saffuriya, located six kilometers north of Nazareth. In 1949, Moshav Tzippori, a Jewish agricultural settlement, was built on Saffuriya’s land, and the olive and pomegranate trees of Saffuriya were uprooted. Tzippori National Park was also established on the land in the 1990s. Though oaks are primarily pictured here, KKL-JNF planted pine trees throughout the destroyed village, part of a widespread practice to serve the Zionist settler colonial nation-building project: the trees cover the rubble, obscuring the traces of Palestinian presence; the protected forests prevent Palestinian return; and the pines recreate a European landscape in Israel. As a number of Palestinians explained to me, the mass afforestation of pine trees has increased the acidity of the soil, which prevents the growth of other kinds of plants.

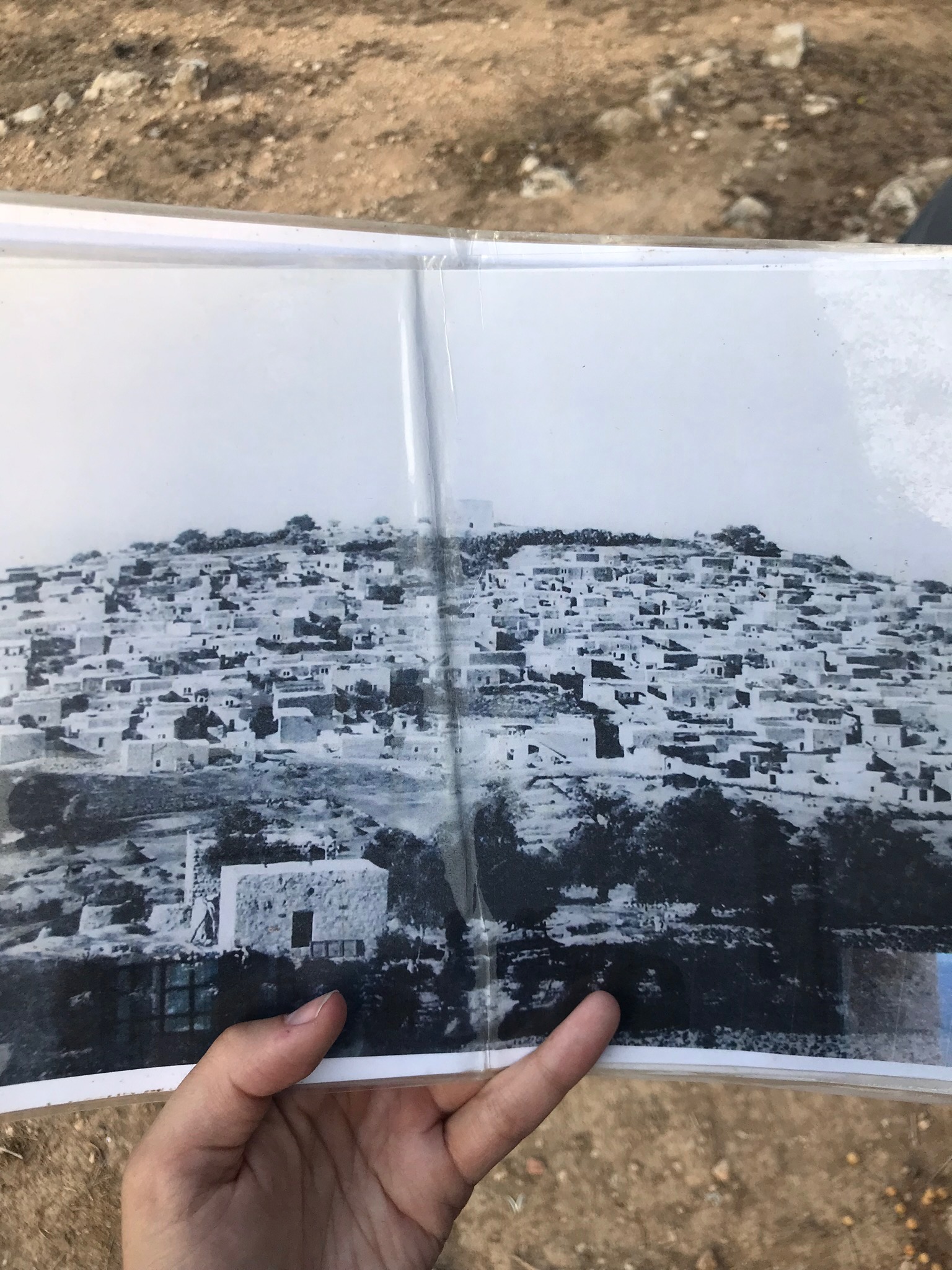

This photo depicts the Palestinian village of Saffuriya in 1931, seventeen years before it was ethnically cleansed. At the top of the hill, you can see a fortress constructed during the Crusader period.

Here is a view of Saffuriya/Tzippori today. The official materials and maps of Tzippori National Park describe the various ruins located within it: the Crusader area fortress, visible at the top of the hill; the Jewish quarter of the ancient city of Sepphoris from the time of the Talmud and the Mishnah (approx. 1st and 2nd century CE); the remnants of Roman buildings and reservoirs; a Byzantine-era synagogue. Saffuriya’s post-Ottoman and pre-1948 history is largely absent from this official narrative, which foregrounds ancient Sepphoris’ connection to the development of Jewish theology.

Palestinian Christians in Bethlehem

Series I:

This is a traditional Christian hosh, or courtyard, in the Old City of Bethlehem – just off Star Street.

It bears the style of traditional 19th century Arab architecture, with several homes converging in a central hosh.

And, as is distinctive of all Palestinian homes in the Occupied West Bank, a large black water tank can be seen, used to keep provisional water for the households. This is because the Israeli government restricts access to public water for Palestinians in the West Bank.

But there is something quite unusual in this hosh: an ancient well, said to be one of the Wells of King David.

King David was the second king of ancient Israel (~1000BCE) and was from Bethlehem. There are many archeological sites in Bethlehem that evince King David’s historical presence in the ancient city.

However, given this, Palestinian Christians also speak fearfully about the historical value of Bethlehem to the Jewish people, and how this may be grounds for its eventual annexation into Israel.

For more than 100 years, there has also been a small altar to King David in one of the hosh’s alcoves.

This is because a number of people – Christians and Muslims alike – have seen a figure or spirit whom they believe is King David. They describe him as a tall man, dressed all in white, carrying incense that smoulders in the wind…

Many local Christians come to visit the altar, light some candles, and ask King David for his intercessory help. Many leave a small donation to the altar’s aging custodian, who has lived in the hosh her whole life, taking care and maintaining the altar.

Series II:

The “Carmel of the Holy Child Jesus Convent” of Bethlehem was founded by St. Mariam Baouardy in 1878. Mariam Baouardy was canonized in 2015 by Pope Francis, and is one of the first saints recognized as Palestinian in the Catholic Church. As such, on the day of her feast (August 26th), many Palestinian Christians in Bethlehem gather at the Carmel convent in prayer.

Mariam was born in the Northern Galilee village of Ibillin in 1846. Orphaned at a young age, she moved to Egypt with her uncle. As her hagiography goes, a Muslim man tried to force her to convert to Islam, and marry him. When she refused, he slit her throat and abandoned her. Mariam was miraculously nursed back to health by a cloaked women, who revealed to Mariam that she was the Virgin Mary. Mariam then joined the Carmelite order and began to receive divine gifts, including prophecy. One of these prophesies was to establish a monastery in Bethlehem. In choosing the land for the Carmel, she was prophetically guided by God to the Hill of King David. The convent’s church and altar were constructed directly above a grotto, where David was believed to have received his royal anointing from the hand of Samuel. However, Mariam did not live to see the convent’s completion; during its construction, Mariam fell down the stairs and broke her arm while bringing drinking water to the workers. Mariam died a few days later from gangrene, in 1878.

The Carmel convent, nestled on the hill of David, is isolated from the business of the city that surrounds it. It is a place of silence and solitude, and a deeply meditative atmosphere.

But on the day of Mariam’s feast, the Convent is anything but – people gather to usher Mariam’s holy relics through the convent’s grounds and beyond, into the city of Bethlehem. The relics, housed in a wooden container, enlaced with mother-of-pearl (a traditional Christian artisanal craft in Bethlehem), are hoisted and carried by members of the Scouts of St. Mariam Baouardy.

Taking to the streets, the Mariam Baoardy youth group lead everyone in singing, chanting and celebrating. Armed with loud speakers, drums and tambourines, the procession leaves the convent and continues through the busy Bethlehem streets into the Old City towards the Church of Nativity – the hallmark of Christian Bethlehem. This performative procession is thus a performance of Mariam’s sanctity and ensoilment in Bethlehem.

Series III:

The cult of St. George is widely observed amongst Palestinian Christians in Israel and Palestine. On the day of his feast, Palestinians flock to his historic hometown of Al-Lydda, or Al-Lod in present day Israel, to visit the Church of St. George.

Because the church falls under the custody of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate, the church follows the Orthodox Rite in liturgy; this takes place behind the large iconostasis that encompasses the church’s sanctuary.

However, Palestinian Christians of other denominations also visit the church, as do local Muslims, who associate the saint with the figure of Al-Khidr, a mystic prophet whom the nearby mosque is also named after.

Beneath the church is the crypt and sarcophagus of St. George. On the day of this feast, his relic miraculously gushes oil – myrrh. Palestinian Christians gather around with empty water bottles, to collect some of the miraculous oil from the holy relic of St. George, to which they add holy water so it can be collected easily.

St. George’s hagiography details the life of a Roman soldier, born in Al-Lydda, who converted to Christianity and died as a martyr for his faith. The fact that St. George was born in historic Palestine is what most sanctifies his presence for Palestinian Christians. This site of the Church of St. George, and the relics it houses, has long been place for Christian pilgrimage (dating to 518CE).

Outside the church, people gather to watch numerous “scout” troupes perform in marching bands, as part of the celebrations. Scouts are organized by church denomination and community – so there are Orthodox, Catholic, Syriac and even Muslim scout groups. This is part of the cultural legacy and history of the British Mandate, when Palestine’s British rulers imported scouting to Jerusalem.

However, the joyous festivities are interrupted by the jarring presence of political posters, protesting the recent actions of Greek Orthodox Patriarch Theophilos III. The Greek Orthodox Church has come under attack by its local Palestinian Christian congregation for having sold church lands in Jerusalem and elsewhere to private Israeli buyers and politicized Zionist settler groups.

Bibliography

Canals, R. (2018). The mirror effect: seeing and being seen in the cult of María Lionza (Venezuela), Visual Studies, 33:2, 161-171, DOI: 10.1080/1472586X.2018.1470902

Canals, R. (2010). “Studying images through images. A visual ethnography of María Lionza’s cult in Venezuela”, in Spencer, S. (ed.) Visual Research Methods in the Social Sciences, p. 225 – 238. London: Routledge.

Mitchell, W.J.T. (2004). What do Pictures Want? The Lives and Loves of Images. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.